With Great Power Comes Great Violin Strings

by

As you may or may not know, I was a violinist well before I was a scientist. For some reason, teachers are much happier to put a violin into the hands of a six-year-old than they are a pipette or a beaker full of hydrochloric acid. Parents, on the other hand, are generally less impressed, especially when said six-year-old is encouraged to practice at home (a.k.a. impersonate a dying cat) for at least 20 minutes a day. But eventually I managed to make the tune of “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star “ discernable from the other strange sounds emanating from my violin, and I’ve been playing ever since.

As you may or may not know, I was a violinist well before I was a scientist. For some reason, teachers are much happier to put a violin into the hands of a six-year-old than they are a pipette or a beaker full of hydrochloric acid. Parents, on the other hand, are generally less impressed, especially when said six-year-old is encouraged to practice at home (a.k.a. impersonate a dying cat) for at least 20 minutes a day. But eventually I managed to make the tune of “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star “ discernable from the other strange sounds emanating from my violin, and I’ve been playing ever since.

“What does this have to do with science?” you ask. Not much. It does however explain why I found the following headline interesting:

Scientist fiddles with spider silk: Filaments are bundled, processed, and played on a violin. (ScienceNews.org)

Spider silk violin strings! Cool!

So I dug out the paper that was published this month in Physics Review Letters and sure enough, a scientist from Japan, Shigeyoshi Osaki, used spider silk to make violin strings.

There has been a lot of interest in using spider silk for various applications, including rope manufacturing and developing Kevlar-like fabrics that are exceedingly strong. Unfortunately a single spider doesn’t make that much silk, and housing a whole herd (I don’t think that’s the correct collective noun, but it conjures up a great visual) of spiders is more troublesome than you’d think, as they tend to eat each other, but there is a lot of work being done on the preparation of spider silk using molecular genetic techniques.

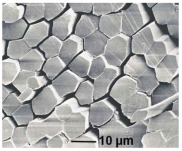

A cross section of the violin cable

In this instance, Osaki took spider silk from 300 female spiders (Nephila maculte), and arranged the 9,000 (for an A string) 3 feet-long strands in a parallel array. He then twisted the strands together to form a cable. This initial cable had lots of space between the strands, which would make it easily breakable, so he kept twisting and coated the strings with glycerol. When he looked at a cross-section of the resulting cable by electron microscopy he saw something surprising; the originally cylindrical silk strands had formed polyhedral shapes that fit together like crazy paving.

This in itself was a completely novel discovery in the world of spider silk research, and has the potential to change the way the material is used for other applications, but in the violin-string world there was still a crucial experiment left to do. Osaki needed to know if the strings sounded good.

So he manufactured a D string (12,000 strands) and a G string (15,000 strands) and assembled some professional violinists. He had them play either the Dancing Master’s Violin 1720 ‘‘Gillott’’ by Stradiviari (recognized as one of the best violins on the planet) or a run-of-the-mill violin strung with spider strings or conventional strings. While the professionals could perceive only a small difference on the Stradivarius, the spider strings made a vast improvement to the regular violin.

As to why these spider strings sound so great, Osaki suggests that “[t]he properties of spider violin strings can be ascribed to their elasticity, high modulus, and mechanically high strength that are characteristic of spider silk.” The timbre of the strings is affected also by their different and numerous overtones.

For the moment, spider violin strings are a novelty, and it will probably be a very long time before the likes of me get to string their violins with them. But we can search YouTube and find examples of them being played by others. Enjoy!

.

Katie Pratt is a graduate student in Molecular Biology at Brown University. She has a passion for science communication, and in an attempt to bring hardcore biology and medicine to everyone, she blogs jargon-free at www.katiephd.com. Follow her escapades in the lab and online on Twitter.

.

Be the first one to mind the gap by filling in the species of the spider as a comment and get your name in the blog along with a sweet new BenchFly mug!

About the prize: In addition to fame and glory beyond their wildest dreams, winners receive our new hot-off-the-presses large (15 oz) BenchFly mug to help quench their unending thirst for scientific knowledge… or coffee. Check out where the mug has traveled – will you be the first in your state or country to win one?

Miss a previous edition of Mind the Gap? Shame on you! Don’t worry – we’ve got you covered:

All the Better to See Sperm Whales With, My Dear

Saw VII: The Revenge of the Sawfish

Caution: Objects May Appear Larger Than They Really Are

Facebook Updates: The Good, The Bad, and The Vague

Scared of Dropping the Soap? Worry No More.

A Social Network for Food: Why Won’t Vanilla Friend Garlic?

I’d Rather Die Fat and Young than Old and Skinny

Look Into My Wide, Vacant, Eyes

Sweet Relief: How Sugar May Help Reverse Climate Change

2footgiraffe

wrote on April 18, 2012 at 2:24 pm

It is a Nephila maculata. :)

alan@benchfly

wrote on April 18, 2012 at 2:34 pm

Bingo! We've got a winner!

Michał Bojarski

wrote on April 18, 2012 at 2:27 pm

Easy one, the spider species name is: Nephila

maculata